The press has claimed that Pierre Lamalattie had inspired to Michel Houellebecq the hero of “La Carte et le Territoire” (“The Map and the territory”). For twenty years he was the accomplice of the writer, to the point that they published together the literary review Karamasov and the painter incarnated a mad artist in a film made by the future Goncourt laureate. Since then, Pierre Lamalattie has been moving more independently, and has a liking for both the map and the territory… of the littoral of Patagonia.

Pierre Lamalattie depicts a society where economy has pride of place, which goes right to the essential: painting allows to grasp instantly an immediate presence, which may be the reason for the discoloration of his paintings, in bluish grey hues. In spite of the usual formula “Any resemblance with actual persons is purely coincidental…” we recognize a neighbor, a cousin, a head clerk, a cashier… This is because Pierre Lamalattie paints prototypes while taking as a starting point a now pervasive practice: resumes. They condense the persons’ experience in a few lines and a photograph, without any irrelevant details.

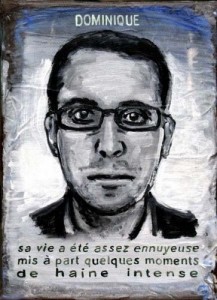

Lamalattie launched into a kind of census by painting portraits which combine a face and a sentence, a summary of their past life, their vocation. To seize their essence as with pincers, the painter achieves a synergy between image and text beyond the degree of calculation found in actual resumes. First of all, it is rather humorous: Jean-Paul is an early riser, which seems plausible from his looks. What a tragic epoch, which thinks it is possible to summarize someone’s life around a major contradiction! Thus the not-aptly-named Pâquerette (Daisy) (since, in French, Pâques means Easter): “She does not imagine anything, not even her resurrection”. Very often there are, at the same character, an explosive mixture between high aspirations and renouncement.

The professional world is also targeted, especially executives. Gabriel, with glasses, short hair, in a sweater, with unhooked shirt collar: “On the profile survey, he was seen hesitating before ticking the ‘leader’ box”. Patrick, bald, sixty: “After a personalized study, he was proposed a degressive bonus”. Sometimes assonances are used; Thibault in a suit rimes with “he immediately had a mindset for promo(tion)”.

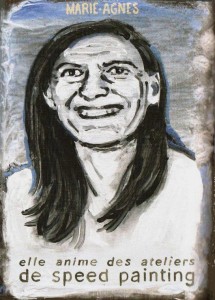

Psychoanalysis is the target of mild criticism: Marilou, brown haired pulled backwards, 30; “She used to bear a grudge against her parents; now against everyone”. Or with Brigitte: “Her psychologist incites her to become herself, but that does not interest her”. The name of smiling Odette rimes with retraite (retirement); “The present annoys her but the future worries her”. Couple life is a relevant social topic, including for Anne-Marie whose “marriage was a kind of getting a permanent job”. New conformist attitudes are pointed out laconically. Paula, with a squaw’s head and showy earrings, will not question contemporary art because “admittedly it is very boring, but she insists on living with her time”. Artists or art lovers are in the firing line, like Bernard: “his bidimensional production tries to constitute a personal work starting from the question of what is given to see”, but there is even more pedantry about Pierick: “his exhibition proposes nothing less than reinvesting in a non-linear way the metacriticism of representation”, or Gottfried, Jörg, or Jeff. Marie-Agnès “runs speed painting workshops”, about which she has an ear-to-ear smile.

The text-image association diverts the efficiency of advertising, headlines and cartoons, and shows the capacity of painting to absorb the best from other disciplines. An untitled painting is terribly drab, being reduced to a number. The title is often the key of the image. Thus the Inquisition found a Last Supper painted by Veronese a little too festive for the circumstances; the painter had only to rename his painting “Dinner at Levi’s” and frowns changed into applause. Lamalattie thus integrates the title into the picture and puts aside an illusion of modern art, namely, that painting is so autonomous from reality that it does not need a title. With Lamalattie, the pictures are called Janine, Guy-Albert… but Ludivine, Jean-Seb and others are no hurricanes – just an unsettling vision of society …

Bertillon and his frontal or sideway anthropometric portraits are a remote ancestor, as evidenced by the painting Human Resources. Like Bertillon, Lamalattie is a master of suspicion: the smile displayed by these apparently satisfied egos is suspect. The painter is a continuator of La Bruyère. “I took a feature here and a feature elsewhere; and with of these various features which could be appropriate to the same person, I produced plausible portraits […] My portraits necessarily give a good expression of man in general, since they resemble so many private individuals”, wrote La Bruyère in Les Caractères (The Characters), where he, too, used maxims… Sometimes the key sentence leaves the impersonal tone for an “us”, a collective point of view, as if the painter were the spokesman of the visitors to the character, such a Bruno: “He told us that in plasturgy one has to adapt”.

Lamalattie does not exempt himself from the lot of his contemporaries. A Pierre curiously resembling him has two occurrences among the 121 resumes*, is the only person quoting in Latin (is painting an extinct language?), and about beautiful Laura, he exceptionally uses a very subjective “I”. “I immediately understood that there would be some trouble with her…”. A self-portrait of the artist as a discrete moralist who comes to conclude (temporarily): “only the FRAC (Arts Endowment) of Patagonia is appropriate for his immense melancholia”.

Christine Sourgins

art historian

*121 curriculum vitae painted by Pierre Lamalattie, préface by Françoise Monnin, Revigny-sur-Ornain, Martin Media, 2010